- Home

- Paul French

City of Devils Page 2

City of Devils Read online

Page 2

While other Shanghailander girls had been shipped out—down to Hong Kong, away to far-off Australia—she had stayed. Her father believed in Shanghai, believed the Japanese would want it to remain a special place that generated profits for them. Therefore they would leave it alone, ring-fence it, and let Shanghai do what it had always done: make money. She believed that too.

And so she had remained in the Solitary Island, and found it a surrounded citadel where those who could afford it continued to dedicate themselves to pleasure as the rest of the world burned around them. This was Shanghai in 1941, and she was part of it.

A chill Shanghai February, close to midnight. Alice arrives at Farren’s on the Great Western Road, her favourite nightspot, supposedly the largest in the Far East. The place enthrals her. After the Japanese invaded the western districts of the city and allowed the cabarets, casinos, dope dens, and brothels of the Badlands to spring up cheek-by-jowl alongside the streets and boulevards of the Settlement and Frenchtown, she had begun making excuses to avoid the stuffy drawing room soirées; the boring tittle-tattle of lunchtime tiffins and Frenchtown cafés. What she discovered, under the neon lights, beyond the velvet rope, was Farren’s and its three floors of roulette, chemin de fer, and craps.

She is known here, treated with respect, among people who feel the same thrill. The young Austrian refugees who man the doors swing them wide open and usher her in with exaggerated bows and cheeky winks. The head doorman, Walter, a great bear of a Viennese but always charming, helps Alice out of her fur as a coat-check girl has a hanger ready. He motions her towards the bar, where Joe Farren, the patron of the club and master impresario of Shanghai’s wartime nightlife, pours her a glass of champagne from an ice bucket that stands on the corner, always full, ready for Dapper Joe to toast his most favoured clientele. He kisses her cheeks and raises his own glass. They clink flutes. He whispers in her ear over the sound of the band whipping up a storm on the dance floor. She doesn’t quite hear what he says but nods and smiles. With Gentleman Joe it’s always compliments.

Alice moves through the diners and dancers, those left in Shanghai lucky enough to be able to afford steak and champagne, to shrug off their cares and dance. It’s a dwindling group, but those best able to party and gamble come to Farren’s. She heads up the staircase to the gambling floors and makes for the roulette tables where her cohort of fellow gamblers gathers nightly. Alice favours roulette, a game of pure chance that rewards only those willing to believe in the long odds and with the money to stay in the game all night. It is always surprising that so many in Shanghai, a city that few bet on surviving much longer, should worship at the roulette table. But the tables are packed. There are no spare stools, though she knows they will always find a place for her.

Usually she would begin her evening talking with the pit boss, Gentleman Joe Farren’s partner, Jack Riley. Where Joe is suave, all middle-European elegance, Jack is American bluntness with a rough charm. But she knows Jack wouldn’t be around tonight; she’d heard Jack had trouble with the courts and was lying low. Some thought he’d skipped town; others that he was hunkered down over in Hongkew, up by Little Tokyo, and wouldn’t be reappearing anytime soon as the law, or what was left of it in Shanghai, had sworn to jail him.

She stops to drink a good-luck toast with a few friends who also spend their evenings at the Farren’s roulette tables. Then she decides to see if the gods of good joss are with her that evening and heads towards the table. Albert Rosenbaum, Jack’s number two and stand-in pit boss, sees Alice and winks. He taps the shoulder of a Chinese dandy and whispers in his ear. The dandy has been betting low amounts and coming up evens, so neither he nor Farren’s is ahead. The dandy refuses the croupier’s offer to bet and decides to call it a night, pocketing a few chips in a pile that Rosenbaum has added to as an incentive to vacate his place. Rosenbaum motions to Alice to take the vacant spot. He places a pile of chips on the table for her, and she sees him make a note in his little notebook of the amount. A good pit boss always makes sure the regulars with money to burn have chips in front of them.

Alice sips the last of her champagne. She nods to Joe as he comes up the stairs from the bar and heads up one more flight to his top-floor private office with Rosenbaum.

Suddenly, she hears shots and screaming from downstairs. She knows what’s happening. This is the Badlands; desperate gunmen had raided other nightclubs and casinos. She watches the players at the next table scramble underneath. Then more screaming, shouting, glass shattering. More gunshots, this time on the gambling floors. A light fitting shatters; wood splinters fly as a shot hits the wall opposite the roulette table. She hears footsteps heavy on the stairway and turns round. Alice is surprised to see Jack Riley, shotgun in hand, with his German bodyguard, Schmidt, waving a Mauser, scattering people looking to get down the stairs. Jack shouldn’t be here; the police are hunting him; he is Shanghai’s most wanted man. He smiles at her, his usual broken-tooth grin she knows so well. He looks embarrassed, and then he looks away. Jack and Schmidt point their guns up at the ceiling and fire. Croupiers are diving for cover. Jack glances back at her momentarily. Then she feels a sharp burning sensation in her back and falls to the floor.

March 28, 1941—Young Allen Court, Shanghai International Settlement

Alone and friendless, Jack Riley is holed up in the Young Allen apartments on the Chapoo Road, Hongkew. He is not so Lucky Jack now. Only the vast stretches of Shanghai’s Eastern District—Hongkew, Yangtzsepoo, the Northern External Roads—offer the possibility of sanctuary. This is predominantly Chinese Shanghai, effectively outside Shanghai Municipal Police day-to-day control. It’s policed by the Japanese, its northern edge raked by Imperial Japanese Army snipers and trashed by civilian Japanese looters who call themselves ronin. Hongkew is now inhabited only by transients, Chinese refugees from the countryside, Japanese army deserters, and marauding pi-seh hoodlums for hire. Jack is on the lam and paying over the odds, in cash daily, for the flop. Everyone knows he’s on the run, the newspapers revelling in the fact that, finally, the odds are stacked against the Slots King of Shanghai. His crew, dubbed Riley’s Friends, have evaporated. All of his former allies are in the wind.

Shanghai is a dead end, a lethal cul-de-sac. There’s no way out. No white man would last five minutes in the occupied countryside outside the city, where Japanese Navy bluejackets roam. The sea is twenty Jap-infested miles downriver, and the Whangpoo River is on lockdown, with Little Tokyo’s marine gendarmerie on patrol. Frenchtown is too small, with too many enemies—the Sûreté, the Vichyites, the Frenchtown Corsicans he’s crossed before. The Badlands is crawling with trigger-happy, dubiously fresh-badged faux-police goons of the Chinese collaborators and nasty Japanese Kempeitai, Tokyo’s homegrown version of the Gestapo, military police fingernail pullers, who’d love to give him a beating and then claim the bounty. They used to smile like friends, take his fat envelopes stuffed with cash, break bread and parley. Every last one of them knows Jack’s mug intimately—they took money off him for long enough. Jack won’t get any help from the Shanghai Badlands Syndicate either. Thanks to him, it’s over. He’s interfered with business, broken rule number one: don’t draw undue attention.

It’s not that he doesn’t have regrets; it’s just that he doesn’t have many. He feels bad for not having treated Babe and Nazedha, the only two real women in his life, better. He wishes things had worked out better with Joe. He can’t get the image of that girl, Alice, out of his head, at the roulette table, falling down to the floor, her eyes on him all the time.

So here is Jack, among the rubble and the smouldering timbers, the result of Imperial Japanese Navy bombs aimed at the main railway line out of the city. The room is bare, cold, the fireplace useless, even if he had coal—and nobody without serious connections in Shanghai has had coal for months. He’s left with a Japanese hibachi stove and precious little charcoal to fuel it. The place reeks from his chamber pot, the toilet broken. An iron bedstead, an ancient mattress mad

e rancid and lumpy by a thousand arses, a thin red eiderdown that’s never seen a laundry. A little balcony, but he dare not show his face. Late at night he hears the ping of the solitary shots from Type 97 sniper rifles picking off poor indigents out scavenging firewood. Their bodies are left in the street. The first night he woke up scratching, the wallpaper covered with bugs, a seething mass. He sleeps fully clothed, but the lice get in anyway, marking his arms and legs like the worst kind of track marks. Jack never took to the toot juice or the needle; he was always a caffeine and Benzedrine junkie. He’d kill for a cup of joe now, and he’s down to a handful of bennies his old squeeze Babe cadged for him under the counter at the Sine Pharmacy on the Hongkew Broadway. He knows he has to stretch them out to keep alert and stop the tremors from kicking in.

He is too well known to leave the building—who doesn’t know Slots King Jack’s trademark chipped-tooth grin? Every schmuck who ever bought a two-cent beer or a dollar hooker down at the Jukong Alley brothel shacks, or cruised Avenue Eddy for better-class working girls, or took in the floor show at DD’s, ritzed at the Paramount, spun a wheel at Farren’s, bet on the mutts at the Canidrome, attended the Friday night fights in Frenchtown, watched the baseball, caught the super fast Basque boys at the jai alai, shot the shit at the Fourth Marines Club, slummed it in the Scott Road Trenches or huddled out back of Blood Alley for the bareknuckle Square-Gos knows him, every single one of them now a betrayer.

There are rifle butt–sized holes gouged in the masonry where the Japanese used the building to snipe Nationalist soldiers in ’37. He can’t bathe or shower and uses an increasingly blunt razor to shave his face. He is deteriorating and he knows it—his collar grimy, cuffs filthy. His teeth ache, his gums bleed, and the cold makes his fingers hurt. Jack Riley is, for the first time in a long, long time, desperate.

Crouched by the window he hears the end, the growling engine of the Red Maria. Men spill out the back, taking up position in full body armour—they’re expecting him to shoot it out. The Municipal Police riot squad has come with wide-bore guns, the safety catches flicked off, corporals shouldering ugly Chinese knockoff Mauser M.1896 semi-automatics with broom-handle grips—old-school and nasty. There are huge white boys with the red hair of Ireland, the meanness of Ulster, and the menacing grins of England; oilskin-clad Sikhs standing ramrod straight, handpicked for the elite squad and armed with .303 carbines. Snipers take up positions, alongside a man with a teargas bomb.

The Young Allen apartment complex is strangely silent. The riot squad won’t hesitate. Their standard orders? Shoot to kill, then count to ten. How the hell had it come to this? Jack slides under the bed frame in the hope it’ll offer some protection. He stares up at the rusty springs of the iron bedstead; he can almost feel the men’s fingers caressing the triggers outside. Maybe he’ll be Lucky Jack just once more … before it all gets shot to shit.

PART ONE

The Rise to Greatness

Shanghai is a big city. It is a modern city. It is also a unique city. Its up-to-the-minute citizens live in skyscraper apartments and pent-houses, listen and dance to the latest in swing music.

—China Digest, 1940

Shanghai: saturated in riches and crimes, in vanities and vices, in miseries and poisons …

—Marc Chadourne, Tour de la terre: Extrême-Orient (1935)

Let us sing of that old tavern, where dark Louis used to dwell

Where the Olgas and the Sonyas cast their spell

Of Whitey Smith, Bo Diddley and the little Carlton girl

Of Joe Farren and his own sweet Russky Nell

—‘Maloo Memories’, a pastiche of an old Shanghai Volunteer Corps song

1

Born Fahnie Albert Becker, the custodians called him John. His origins were a subject of rumour and conjecture, an ever-changing story as the years and then the decades passed. But the man who would be Jack Riley to all in Shanghai was probably born in a Colorado logging camp near Manitou Springs in 1897, the son of a certain Nellie Shanks and Albert Azel Becker. His old man, a violent alcoholic, was gone before his son’s first birthday. His mother, broke and deserted, dumped him in a Tulsa orphanage, where the custodians beat the boys and left them hungry at night. Becker decided to bail when he was seven. He bummed around and somehow reached Denver, where he got a job polishing brass and emptying spittoons in a nightclub, sleeping out back; the joint was part casino, part dive bar, part brothel.

At seventeen he found a home and a family in the United States Navy. He shipped out of San Francisco for Manila on the U.S.S. Quiros as an apprentice seaman for two years on Yangtze Patrol, the ‘Yang Pat’ of the United States Asiatic Fleet. The Quiros was part of a squadron that patrolled upriver from Shanghai to Chungking and all ports in between, protecting U.S. citizens and interests, guarding the tankers of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, the up-country terminals of Texaco, and the packed warehouses and go-downs of British-American Tobacco.

Discharged in 1919, Becker couldn’t think of anything better to do than re-enlist for another tour, this time Manila to Shanghai. Nights off he spent playing craps in the Hongkew and Chapei sailor bars and drinking along Blood Alley with money won in prizefights out back of the bars. Righteous bucko mate, rated fighter, all-round good guy. Then he was back aboard and upriver to Wuhu, Nanking, and Chungking, his downtime spent boxing on deck, going ashore to play baseball, or shooting craps in the mess. The Yang Pat rotated and the Quiros headed home. John Becker was honourably discharged in 1921.

John Becker stepped ashore in San Francisco and wandered the port towns of California, staying in one-night cash-only flops, eating corned beef in sawdust-floored restaurants or chop suey in all-night Chinese diners, oyster shells crunchy underfoot. Then came Prohibition, and he switched to speakeasies and shebeens, sucking down rotgut hooch, sandpaper gin, and near beer. Eventually he ran out of money and headed back to Oklahoma, to Tulsa County; the only city he could vaguely call home, though his memories of that orphanage and the violent custodians were far from warm.

He got a gig at a taxi company. He knew engines, and the company could save a mechanic’s wage by having him service his own vehicle. In 1923 Becker was still driving drunks home on the late shift, but he knew for sure Tulsa was a bust. Darktown was in cinders after the Greenwood race riots, and crime was out of control.

One night he picks up two guys at the Cave House speakeasy out on Charles Page Boulevard. It’s a good fare, and Becker has been drinking and feels like he can handle these boys. When they get to the destination, a house in the suburbs, the men tell John Becker to wait while they pick something up, and then they’ll head back to town. The meter’s still running, he’s supping a quart of rye, so what the heck. The men walk up to the house across the lawn, the outline of their hats visible as they open the door and smoke wafts out into the dark night air. There’s shouting, commotion, and a shot; the men come out fast, dragging a third who doesn’t look like he wants to leave.

If you believe John Becker, he didn’t know anything till he heard the shouting and the shot. The men threw the third in the back and jumped in, punching the daylights out of the poor sap. Becker drives them to another house, and they drag the beaten guy in with them, but not before one of the men hands him a hundred-dollar bill and tells him to vamoose. The next day the cops show up and bust Becker for kidnapping. His fare had boosted an illegal dice game, killed one of the punters, and kidnapped another. There’s a kidnapping epidemic in the Midwest, and it’s re-election year, so the judge is not inclined to go easy. John Becker goes down for thirty-five years in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, McAlester.

His civvies are confiscated, his head shaved to prevent lice; he’s fingerprinted and photographed. On the cellblock: big guards with black batons; seven-by-three-foot cells; a disinfectant-filled bucket for your shit; a deafening siren in case of escape or riot; bad, bad food; men praying; hardened cons deranged with untreated syphilis, sobbing for their mamas; the mad and the bad of M

cAlester.

Becker plays dice for smokes. He becomes a trusty and gets a job in the shop. An old lag shows him how to make a pair of loaded dice that will always come out the way you want, if you learn to throw them just so and distract the heels. Those hours of pitching with the Yang Pat crew prove useful; he becomes the starting pitcher on the prison baseball team. They head for an out-of-pen game in McAlester City, and when the team heads one way with the guards, Becker heads the other. Walking away, the sweat streaming down his back, he waits for a guard’s bullet to smash into his spine. Not running, not turning back, heart beating fit to jump right out of his chest. But the bullet never comes. He hops a freight running the St. Louis–San Francisco line. He’s just skipped out on the lion’s share of a three and a half decade stretch.

On the run, he’s in a San Francisco boardinghouse down on the Embarcadero—as far west as you can get without swimming. He’s spent nights in hobo camps where nobody asks your name. Now he needs to hunker down, stay out of sight, hope Oklahoma forgets about him. He knows he got lucky; he got a second chance. He quits the booze and the smokes—no profit in either. He rolls a drunk tramp on the waterfront and nabs his papers, and he’s Edward Thomas Riley now. Fahnie Albert Becker is history. He likes Jack better than Edward, thinks he’ll keep the T, and Riley suits just fine too—anonymous, everyday, all-American. There must be thousands of Jack Rileys out there. But some things are more difficult to change than your name.

Jack sits at a small table, rolls up his sleeves, and pours caustic soda in a glass. He takes off his leather belt and puts it between his teeth, then lays two hand towels out next to the glass. He takes three deep breaths, looks out the window at the scrappy backyard of the boardinghouse, and dips the fingers of his left hand in the chemical mix. The acid burns, and he snorts through his nose, forcing himself to dip each finger, then switches to his right hand, breathes really deeply, and repeats the process—thumbs and all. He takes his last finger out and relaxes his jaw, lets the belt fall out on his lap. He manages to wrap the towels around his hands and staggers over to the bed. He lies there for days, in satisfied agony. The whorls on his fingertips are gone, and they slowly heal and harden into callused skin. It ain’t pretty, but he’s a new man with a new start. He signs on as a mechanic with a tramp freighter heading across the Pacific to the Philippines.

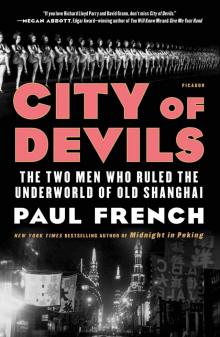

City of Devils

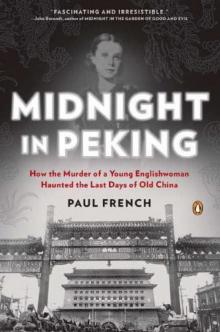

City of Devils Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China