- Home

- Paul French

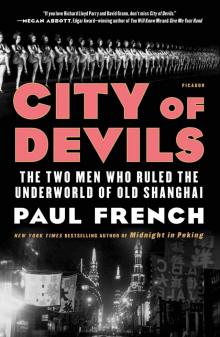

City of Devils

City of Devils Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Photos

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Picador ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For A.V.W.

The conduct of the people was so indescribably frightful, that I felt for some time afterwards almost as if I were living in a city of devils.

—Charles Dickens

Shanghai was a city of vice and violence, of opulence wildly juxtaposed to unbelievable poverty, of whirling roulette wheels and exploding shotguns and crying beggars … Shanghai had become a tawdry city of refugees and rackets.

—Vanya Oakes,

White Man’s Folly (1943)

Shanghai. A heaven built upon a hell!

—Mu Shiying,

Shanghai Fox-trot (1934)

Truly the devil pulls on all our strings.

—Charles Baudelaire

PREFACE

I lived in Shanghai for many years. Daily I walked the city’s streets, soaking up its unique atmosphere. Despite the myriad skyscrapers and overhead expressways, I spent my spare time looking for traces of what had been before, wandering a city of ghosts and trying to recapture the lives of those foreigners of so many nations who once knew the International Settlement of Shanghai as their home. In the last quarter of a century, Shanghai has become a city reborn. In the early 1950s, a virtual dust sheet was cast over the port, and little changed for more than forty years. It was only in the mid-1990s that Shanghai was allowed to thrive again. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century I lived in a city that was building at breakneck speed, bulldozing the old and well-worn seemingly without a care, keen to construct the new and shiny as fast as possible. But an older city still, just about, exists.

It’s easy to succumb to nostalgia in Shanghai. The metropolis is constantly eroding the built environment of its past. It is rapidly losing the last remnants of both its art deco and modernist architectural heritage, as well as its traditional narrow, confined rookeries and alleyways, shikumen stone dwellings and lilong lane houses. Periodically Shanghai does try to recall its previous heyday between the world wars, but every renewed bout of nostalgia becomes more disconnected, more affected by hindsight. It takes increasing amounts of imagination to catch a glimpse of the old glamour and style of Shanghai (best done at twilight or dawn, I find) down an alley, in the lobby of an old building, along the banks of one of the city’s creeks and streams. In my effort to understand what the city’s inhabitants once thought and why they acted as they did, my quest has always focused on the lower depths of this once remarkably cosmopolitan city, Shanghai’s foreign underbelly: those rarely written about, the men and women not covered in glory or fabulous riches, not feted or even remembered in the minutes and formal records of the city. I’m drawn to the flotsam and jetsam, the impoverished émigrés and stranded refugees, transient ne’er-do-wells and washed-up chancers, con men and female grifters. I seek out those foreigners who came to the China Coast and preferred to exist in the city’s criminal milieu, to disappear into its laneways and backstreets. They’re not distinguished or heroic. Invariably they’re liars and cheats. They’re rarely anything close to good, and all are terribly flawed, often living in Shanghai because they were one step ahead of the law and, invariably, other options were few and far between. But many of them had a certain style, panache; their own particular flair. They take a lot of seeking, but their traces—faint, sketchy—remain.

City of Devils is based on real people and real events, as best as can be divined from the witnesses, participants, and reports of the time. A complete record is impossible due to the nature of the people involved, their somewhat clandestine lives, purposely hidden pasts and false names, changed birthdates and the crimes they committed and/or abetted, all of which they would never willingly confess to. Where records do exist, they are rarely as complete and as detailed as the academic historian would accept—falsifications, clerical errors, and downright lies were exacerbated by war and devastation. Although assumptions have been made, I’ve done my utmost to adhere to historical accuracy. Of course all the main players are now gone, though I am sure they would have denied everything, just as they did at the time.

This story is drawn from a wide variety of sources, primary and secondary. As we are now three quarters of a century distant from the finale of the events in this book, primary sources are difficult. Fortunately, some people who lived through those times still remain with us, while others told their stories to their children and grandchildren—they are thanked in the acknowledgments. I trawled through a large range of secondary sources, including the archives of the Shanghai Municipal Police and the Shanghai Special Branch, the annual reports of the Shanghai Municipal Council, the archives of the British and American consulates, the records of the U.S. Court for China at Shanghai and the archives of the United States Marine Corps. I also drew upon the China Coast newspapers and periodicals of the time, especially the China Weekly Review, China Press, North-China Daily News, Shanghai Times, Shopping News, Peking and Tientsin Times and Walla-Walla (the magazine of the U.S. Fourth Marines in Shanghai). The excerpts from the Shopping News that appear in the text are genuine historical articles from the publication, with one or two minor additions in the interest of advancing the narrative.

I have tried to recreate the linguistic Tower of Babel that was the treaty port of Shanghai between the world wars. As well as English (in its British, Irish, American, and Australian variants), other commonly spoken languages were Yiddish, German, Russian, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Spanish, as well as Tagalog, Korean, and Japanese. Shanghai was also, of course, a melting pot of Chinese dialects—Mandarin-Pekingese dialect and Cantonese as well as, obviously, the local Shanghainese dialect. I have used the Reverend Donald MacGillivray’s A Mandarin-Romanized Dictionary of Chinese (eighth edition, 1930) to standardise the Wade-Giles system of romanisation. That said, there is no definitive answer to most of these romanisations.

It’s worth noting that most slang, curses, racial epithets, and colloquial words and terms used are specific to the time and place and may, if not viewed in the context of the period and place, trouble modern sensibilities. Throughout I have sought to use those words and phrases most commonly noted in memoirs and newspapers of the time. Many are now deemed offensive, and I have no desire to revive them except in the interest of historical accuracy. Between the wars Shanghai was certainly highly cosmopolitan, but it was, in many ways both formal and informal, segregated between the Chinese and the foreigners. At times the two communities interacted and overlapped—this went for the respective criminal minority as well as the law-abiding majority of the city’s populace—but, for most of the characters in this book, Shanghai was a Chinese city where they invariably worked, played, and committed criminal acts largely with other foreigners.

At a time of ever-escalating inflation in Shanghai in the late 1930s and early 1940s, calculating any prices in the text into today’s money is problematic. Shanghai used multiple currencies and did business in anything considered reliable, from gold bullion to Indian

rupees. The Mexican silver dollar was the most trusted currency during the time of the Badlands and was imported in great volume. The Bank of China issued Chinese one-dollar, five-dollar, ten-dollar, fifty-dollar, and hundred-dollar notes, though inflation made these problematic, as did rampant forgery. Coiners also put out fake coppers—three hundred (real ones) equalled one silver dollar. As a rough guide, Shanghai Mexican silver dollar amounts can be multiplied by six for an approximate equivalent U.S. dollar sum in 2017.

—Paul French, London, August 2017

INTRODUCTION

Shanghai was a prize won after victory in an opium war, a war waged by Great Britain to open China to a drug that caused pain, waste, and death in the Middle Kingdom while enriching the western nations. The foreigners claimed Shanghai as part of their victory terms, cauterised it from the rest of China by a most unequal treaty signed in the face of British gunboats. And so a strange urban aberration grew up on the banks of the Whangpoo River, close to the mouth of the Yangtze River, gateway to the vast Chinese hinterlands. The foreigners who came to build the city described Shanghai as a shining light, an example to the heathen darkness of China of the benefits of free trade and modernity. To others, the freebooting city was little more than a magnet attracting adventurers and ne’er-do-wells; a festering goiter of badness; stolen territory. Yet good, bad, or not caring either way, grow Shanghai did, from walled fishing village in dread of marauding pirates to an international ‘treaty port’ and the world’s fifth largest city by the 1930s—a deafening babel of tongues, a hodgepodge of administrations, home to hopeful souls from several dozen nations joined together by one simple guiding ethos: money and the getting of it. In a hundred Sunday sermons from the missionaries who hoped to bring the light to China, Shanghai was the insanity of Sodom incarnate. Shanghai became a legend: the Wild East. By the 1920s, three and a half million people called the nine square miles of the International Settlement home.

The International Settlement governed itself—not a colony like Hong Kong or Singapore, but a treaty port, a place of trade and enrichment for the conquerors. The Settlement was administered by an elected Municipal Council composed mostly of foreigners—‘Shanghailanders’—and, later, grudgingly a few ‘Shanghainese’ Chinese. The foreign-run Municipal Police enforced the law and, if needed, the Shanghai Volunteers would muster to reinforce the foreign troops stationed in the city to protect the Settlement. The Settlement represented fourteen foreign powers—Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Great Britain, and the United States—who had extracted treaty port rights from a weak and teetering Qing Dynasty China. Each had its own consulate and courts within the Settlement, for within the Settlement a foreigner was not subject to Chinese justice but only to that of his or her own nation. This extraterritoriality meant that an American could only be called before the American court, a Briton before the British court and so on and so on. A mixed court was created to resolve legal issues between foreigners and Chinese, with a foreign assessor sitting alongside a Chinese magistrate.

The French refused to join the Settlement and maintained their own adjacent concession with their own municipal council, police force, troops, and justice system. The vastness of China abutted the foreign concessions to the north and to the west. Those areas, the roads just beyond the Settlement’s borders, became contested no-man’s-lands. As China spiraled downward towards war with Japan, the once leafy and suburban Western Roads area of the city transformed into a ‘badlands’ of gambling, dope, and vice.

Shanghai’s existence was the most direct manifestation of the weakness of the ailing Qing Dynasty—Chinese soil taken by foreign powers. In 1911 the 267-year-old dynasty collapsed, and a Chinese republic was born. That republic descended swiftly to infighting and fratricidal dispute. Warlords rose and ruled giant swathes of China the size of Europe with their own private bandit armies throughout the 1920s. China appeared constantly on the point of collapse, about to fragment into a hundred warring states. Against this chaos Shanghai stood solid, prospered, and grew.

Shanghai between the world wars was a home to those with nowhere else to go and no one else to take them in. Its International Settlement, French Concession, and Badlands district admitted the paperless, the refugee, the fleeing; those who sought adventure far from the Great Depression and poverty; the desperate who sought sanctuary from fascism and communism; those who sought to build criminal empires; and those who wished to forget. The city asked nothing of them, not visas nor money nor status. Shanghai became a city of reinvention. It reinvented old China as something modern, glittering and golden, where a Chinese peasant didn’t have to chi ku, ‘eat bitterness’, as generations of their forebears had, but could grow rich and flourish. It transformed an unwanted orphan, born in a cold-water tenement in the American Midwest, on the run from a maximum-security prison, into a millionaire through slot machines, roulette wheels, and violence. It transformed a hungry and ambitious Jewish boy from the Vienna ghetto, dreaming of an escape from poverty, into a master impresario who created dazzling dance hall spectaculars with chorus lines that rivalled anything New York, London, or Paris could muster, alongside a casino empire such as the Far East had never seen before.

But no city, not even Shanghai, was big enough for all those who sought to profit from it. And so inevitably men, nations, and ideologies clashed in an ever-expanding orgy of violence and retribution, while an invading Japanese army raped and ravaged outside the gates of the International Settlement.

Shanghai was surrounded—by sea to the east and south and by the ferocious pillaging armies of Japan to the north and west. In August 1937, the Japanese bombed the Chinese-controlled portions of the city. They avoided attacking the foreign concession, not yet wanting war with the European powers and America, and so the International Settlement and the French Concession became the ‘Solitary Island’ (Gudao, as it was dubbed by the Chinese). Lines long demarcated and agreed upon were crossed, negotiated spheres of influence were laid to waste, and thousands of innocent people were killed. While the phosphorous flames of the fox demons of war swirled through the burnt-out streets and devastated quarters of the Chinese portions of the city, the Japanese entered the house and took everything. Those who could escape did so, but many were left behind in the City of Devils.

This book is a true account of the lives of two men who inhabited Shanghai in its last, dying days before Pearl Harbor, when it fell definitively to the Japanese occupation. Joe Farren, born in the Vienna ghetto as penniless Josef Pollak, had come to Shanghai as an exhibition dancer and risen to become ‘Dapper Joe’, the city’s own Flo Ziegfeld, running the best chorus lines in the swankest nightclubs, and finishing up with his name in neon above the Badland’s biggest casino. His partner in that last, most lavish Shanghai venture was another man who changed names and identities—Jack Riley, ex–U.S. Navy, wanted prison escapee, who began his China Coast criminal career as a bouncer in the toughest rookeries of northern Shanghai and rose to be the city’s slots king, controlling every slot machine in the city.

Over the years the two men edged warily around each other as they became rich and powerful, as between them they created much of the city’s reputation as an international capital of sin and vice. Joe constantly sought more and accepted the city’s temptations if they facilitated his rise; Jack greedily grasped any and every opportunity that presented itself. ‘Dapper Joe’ and ‘Lucky Jack’ collided, collaborated, clashed, and then made truce and partnered, a thing nobody could have predicted.

In November 1940 they bestrode the Badlands of Shanghai like kings, the streets their kingdom, their gigantic nightclub and casino their palace, while all around the Solitary Island were desperation, poverty, starvation, and genocide. They thought they ruled Shanghai; but the city had other ideas.

This is the story of their rise to power, as part of Shanghai’s foreign underworld; it is also the story of their downfall and the trail of des

truction they left in their wake. Shanghai was their playground for a flickering few years, a city where for a fleeting moment even the wildest dreams seemed possible.

PROLOGUE

The Devil’s Last Dance

February 15, 1941—Farren’s Nightclub, Great Western Road, the Shanghai Badlands

Shanghai is not the city it once was…’ She heard it over and over again, repeated so often it had become received wisdom. At the still-swank cocktail parties just off the stunning waterfront Bund; at dinner parties in the still-elegant apartments and villa houses of the French Concession … Since August 14, 1937, Bloody Saturday, Shanghai was not what it once had been.

She disagreed.

Not that the war, the bombings, the Japanese hadn’t changed things, but that change wasn’t all bad. Shanghai clouds had silver linings. Her father, a bullion dealer, was making more money than ever: inflationary and uncertain times meant demand for gold had soared. The Japanese encirclement of the foreign concessions was an inconvenience; fewer ships came and went; airplane service was erratic to nonexistent. Life in the protected Solitary Island could be tiresome as it meant many of life’s goodies didn’t make it to Shanghai anymore, but nothing was insurmountable.

For Alice Daisy Simmons, just turned twenty-eight, a Shanghailander by birth, unmarried and a partner in her father’s firm, Solitary Island life was exciting. From her Frenchtown penthouse, the wardrobe stuffed with tailor-made gowns and Siberian furs, Alice looked out on a city that twinkled at night like a jewel box. They all knew war raged in the hinterlands, that the wartime capital at Chungking was bombed nightly, that little seemed to stand in the way of the Japanese Imperial Army and their desire to subjugate all China. But here, in Shanghai’s foreign concessions, the neon still shone brightly, taxicabs still hustled for fares, and the nightclubs swung just like before.

City of Devils

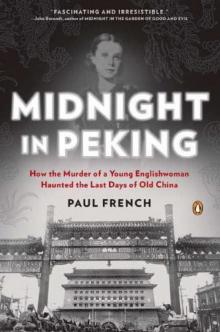

City of Devils Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China