- Home

- Paul French

Bloody Saturday Page 2

Bloody Saturday Read online

Page 2

John Morris left his Buddhist temple phone booth to drive back to the relative safety of the International Settlement south of Soochow Creek. Heading down through Chapei, Morris was surprised to see a lone foreigner walking south and stopped to offer him a lift – Max Hirsch, a German and a long-time resident of Chapei’s Scott Road. Herr Hirsch was ‘nonchalantly’ strolling towards the Settlement border with his three dachshunds.

John Morris dropped Hirsch and his dachshunds off and parked up by the Broadway Mansions, a magnificent art-deco apartment building adjacent to the Garden Bridge, right on the northern bank of Soochow Creek at the junction with the Whangpoo and facing the Bund across. It was home to many foreign journalists. Randall Gould, a former United Press colleague ran an office largely out of his apartment in the building. Gould, a tall Minnesotan, had worked in Japan before moving to China in the 1920s to work for the newspaper. He reputedly knew every correspondent, stringer and hack writer in the Far East and had a network second to none that extended from Honolulu to Yokohama, Manila to Hong Kong, and all points in between. Gould was now the China correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor and the editor of the Shanghai Evening Post & Mercury.

Morris joined Gould on the roof of the nineteen-storey building to watch the Japanese shelling of Chapei and the North Railway Station. They saw three shells fired and fall from the Idzumo, a brief pause for the artillery observers to calibrate the range, and then another volley of shells. The two men watched the Japanese repeat the operation again, and again, and again . . .

Colonel Charles F.B. Price was a China veteran. He had been the Officer-in-Charge at the American Legation in Peking in the 1920s and was now the commanding officer of the one thousand United States Fourth Marines in Shanghai. With the commencement of the Japanese shelling of Chapei, Price recalled his men to the barracks and ordered them to prepare for ‘any eventuality’.

The foreign-manned SVC was summoned on Friday night to protect the forty-nine thousand foreigners resident in the Settlement. The SVC was divided into companies along national and specialist lines. All members were volunteers recalled from their day jobs at times of emergency and were spread out across the Settlement. One and a half thousand SVC members were present in the city to muster themselves immediately. The Shanghai Scottish and Jewish companies were billeted in the Rowing Club adjacent to Soochow Creek, just across the road from the sprawling British Consulate’s compound. The SVC’s Air Defence detachment was stationed close by in the gardens of the Union Church.

Commander Charles FB Price

‘B’ Battalion, composed of the American, Portuguese, Philippines and American Machine Gun companies, had occupied the Polytechnic Public School on Pakhoi Road, close to the Shanghai Racecourse, while ‘C’ Battalion, predominantly manned by White Russian refugees to Shanghai and the only full-time company in the corps, occupied a number of block houses on Elgin Road on the far side of Soochow Creek, close to the North Railway Station. The Russians had immediately begun helping the Chinese Army defend the station to fill canvas bags with sand to barricade their position. A Chinese detachment of the SVC, along with a group of interpreters who aided communication between the linguistically myriad companies, was stationed in the Cathedral Boy’s School in the cloisters of the Shanghai Cathedral on Kiukiang Road. Despite the hostilities with the Japanese Army, the Japanese Company of the Corps had still been mobilised and stationed only two streets away from the North Railway Station on Boone Road.

White Russian refugee Boris Ivanovich was watching a movie that evening at the Metropole Cinema on Thibet Road in the French Concession. Halfway through the night’s main feature – Hollywood Cowboy, a Wild West adventure with George O’Brien – a slide flashed on the screen ordering all members of the SVC to immediately report to their companies for mobilisation orders. Boris felt a chill run down his spine. He was just seventeen years old and had lied about his age to get into the corps. He was one of the newest recruits and still hadn’t been issued with an official uniform. As Ivanovich and the other SVC members in the stalls stood up to leave the cinema, the audience applauded them. Ivanovich’s muster point was close by at the Avenue Joffre Fire Station. He walked the few blocks east along the wide street and reported for duty. He was assigned a bunk for the night and told to await orders.

The authorities in the French Concession announced a general curfew that would go into operation between the hours of 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. from Sunday 15 August until the emergency in Chapei was over. The Shanghai Municipal Council followed suit several hours later, announcing their own curfew regulations to go into effect the following week.

Nicolai Alexandrovich Slobodchikoff was, like young Boris Ivanovich, a White Russian. His family had been one of the many hundreds of thousands who could find no accommodation with the Bolsheviks after the 1917 October Revolution and left the country, becoming stateless émigrés. The Slobodchikoffs had headed east, across Siberia and eventually into China. They had settled in Shanghai along with thousands of other refugee White families. Nicolai had studied mechanical engineering in Belgium, but when he returned to Shanghai, he couldn’t find a job to match his education. Like so many Russians of the middle and upper classes, he spoke fluent French and so joined the French Concession’s police force, the Garde Municipal. On the evening of Friday the thirteenth, all leave was cancelled and Slobodchikoff reported for duty at No.22 Route Stanislas Chevalier, French Police HQ.

Leave was also cancelled for members of Shanghai’s Municipal Fire Service. R. Somers was the Assistant Station Officer at the Shanghai Central Fire Station on Foochow Road, a few blocks from the Cathay Hotel. Close to the offices of the Municipal Council and the headquarters of the Shanghai Municipal Police, the four storey Central Fire Station was crowned with the motto

‘We Fight the Flames’ in Ningbo-glazed green tiles over the red brick frontage. Somers reported for duty, dragged out a camp bed and tried to get some sleep.

That evening the Japanese cabinet in Tokyo announced on the radio that they would order ‘concrete measures’ to be taken to destroy Chinese resistance in Shanghai. Premier Prince Fumimaro Konoye stated that he would broadcast to the nation on Sunday. The title of his address would be ‘The Determination of the Imperial Navy’. Japanese newspapers reported that voluntary contributions to the nation’s war chest from across Japan had exceeded US$2.5 million.

A refugee crisis immediately emerged as terrified and bombed out Chinese from Chapei and Kiangwan attempted to reach the safety of the Settlement. An outbreak of sniping across the North Szechuen Road between Chinese and Japanese soldiers sent civilians scuttling for cover on the busy commercial street. Rents for available rooms in the Settlement and Frenchtown immediately soared – a room that rented for eight Chinese dollars a week on Thursday 12 August rented for twenty-five and upwards the next day. The Shanghai Municipal Police remained on duty at their most northerly station on Hongkew’s Dixwell Road and attempted to locate the legion of fires that had broken out and were left untreated across the northern districts. Fire engines heading towards Chapei from the Settlement were jeered, stoned and barricaded from getting through by the Japanese residents of Hongkew’s Little Tokyo.

On Friday 13, ships took advantage of the eye of the storm to leave port. An exodus of nervous Shanghai-landers, foreign residents of the city, began to board evacuating ships where they were able to. The Japanese passenger steamers Shanghai Maru and Nagasaki Maru sailed in the morning, full to capacity, including many Americans who had decided to head home. The ships, headed for Kobe and on to America’s West Coast, were delayed at the mouth of the Whangpoo by the final effects of the typhoon and Japanese Imperial Navy ships claiming concern for passenger safety.

At noon, all Chinese banks were closed; foreign banks remained open for the time being but convened an emergency meeting to consider a restriction of withdrawals to prevent a panicked run on the city’s money supply.

Firemen try to extinguish a fire in Chapei

The Chinese feared a Japanese naval attack on the aerodrome at Lunghwa. After the liners departed, a line of scuttled ships was sunk across the Whangpoo above the Quai de France (the French Bund), adjacent to Shanghai’s Nantao old town, to prevent any more departures. A further ten steamers, including several confiscated by the Chinese from Japanese shipping lines, were partially submerged, just south of Kiangyin on the Yangtze in Kiangsu Province, blocking river communication between Shanghai, China’s most important commercial city, and Nanking, the nation’s embattled capital.

Saturday, 14 August, 1937

The early morning sky was overcast. The typhoon had not yet passed completely and intermittent rainstorms still blew in from Shanghai along the Yangtze River. Heavy winds and rain lashed the city periodically.

Vanya Oakes hadn’t moved from her lodgings at the Astor House Hotel. For two days she had been out reporting on the advance of Japanese troops across Hongkew and their assault on Chapei. On Friday evening, exhausted and after a long hot bath, she had come down to dinner in the hotel’s famous Grill Room. Several Japanese families had come in to dine but the Chinese staff refused to serve them. The Grill Room’s Swiss maître d’hôtel ordered the staff to serve the Japanese families. The Chinese staff refused and the maître d’ was forced to serve them himself.

Colleagues urged Vanya to move into another hotel in the central part of the Settlement, indeed the management of the Astor themselves were advising people to move out of the precariously placed institution. Oakes planned to report on the fighting in Chapei the next day and decided to stay put. At dawn on Saturday morning, she walked out of the Astor into the streets of Hongkew towards Chapei. She saw,

. . . silhouettes loom out of the darkness, gaunt, grim. Bayonets and helmets – movi

ng. The clank of heavy machinery, the groan of wheels, muffled, ominous, indeterminate sounds. Lying close to the wharves the superstructures of ships showed skeletonized, the noses of guns glowering up into the sky. Thump-clump – thump-clump – thump-clu-u-u-u . . .

The typhoon left a blanket of dark cloud over the Settlement. In his office at Broadway Mansions, Randall Gould had started monitoring the renewed shelling of Chapei at 7 a.m. from his rooftop eyrie and was still there several hours later. John Morris stopped by to see him again but had to leave for a working lunch at the Cathay Hotel with his reporting partner Bud Ekins. Gould stayed behind to keep watch and report on the action. As Morris was leaving, the Idzumo’s massive guns once again opened fire towards Chapei, creating enormous crescendos that rattled his teeth. He encountered Judge Milton Helmick of the US Court for China in Shanghai who was sheltering in the lobby from the bombardment. The two men acknowledged each other (Morris was actually dating the Judge’s niece at the time) and tried to act as if it were just another Shanghai Saturday morning.

Claire Lee Chennault’s plan was to send a squadron of American-made Curtiss Model 68 Hawk III dive-bombers against the Japanese cruisers massed on the Whangpoo, followed by a squadron of CAF Northrop light bombers to target the Idzumo flagship. The Curtiss Hawk was the CAF’s frontline fighter, but could also be used as a dive-bomber with a top speed of over two hundred miles per hour.

Chennault was aware that a Japanese response would come quickly – first in the form of anti-aircraft fire from the Idzumo and ground positions, and then from fighter planes catapulted from the deck of the aircraft carrier Kaga. Chinese aircrews had been trained at Hangchow to fly at seven and a half thousand feet at a set speed. This was clearly too high to preclude the possibility of missing the targets in such a confined area, and risked hitting the crowded International Settlement or Pootung on the far side of the river. The need for accuracy, coupled with the low cloud that day, meant the pilots had to fly at just one and a half thousand feet, a low altitude the pilots had not been adequately trained for. Flying at this level over such a densely populated city was a recipe for disaster even for a highly trained bomb sighter. The crews were ordered to stand ready while Chennault considered his options.

Vanya Oakes may have decided to stay in Hongkew, but others had heeded the advice of their consulates to relocate. Japanese-born Dr Robert Reischauer was a professor of international relations at Princeton. The son of American missionaries in Tokyo, Reischauer was leading a Far East study tour with ten American political scientists. Reischauer and his party had been staying at the Astor House Hotel for their first few days in the city, but he decided to move them across the creek to the Palace Hotel on the Bund, believing it to be a safer location.

After breakfast, they all checked out of the Astor. Taxicabs ferried them and their luggage through the rain across the Garden Bridge, along the Bund and onto the Nanking Road and the lobby of the Palace Hotel, directly across the road from the Cathay. The Palace was more costly than the Astor, but Reischauer planned to stay only one more day before continuing on to Tokyo. The additional safety of being in the heart of the International Settlement, rather than embattled Hongkew, was worth the expense of one night at the Palace. He was assigned a suite on the third floor, his bags were taken up and he settled into his room. He had some time to make notes and read before a meeting at 4.30 p.m.

Photograph of the Bund in The Age, Monday, 16 August, 1937

Just Another Working Day

Shanghailanders generally worked a six-day week with Sundays off. Lucien Ovadia, a cousin of the wealthy businessman Sir Victor Sassoon, was at work in the offices of E.D. Sassoon & Co. on the third floor of Sassoon House, part of the complex fronting the Bund waterfront that included the swank Cathay Hotel. Ovadia was one of the vaunted taipans of Shanghai, the Big Bosses, who looked after the Sassoon firm’s finances across the Far East. Born in Egypt he was of Spanish nationality, educated in France, had lived in London and travelled extensively throughout the Far East. It was often said of him that he was, almost, as cosmopolitan as Shanghai itself. Ovadia was working in his office with the windows open in order to catch the wind coming in from the Whangpoo River and take the edge off the stifling indoor humidity.

Frank J. Rawlinson, an American protestant missionary who had been in China since 1902 was now sixty-six years of age. Shanghai had been his home for thirty-five years. On Saturdays he invariably worked at the Missions Building on Yuan Ming Yuan Road, close to the Bund and just behind the British Consulate. Around thirty different missionary societies shared offices in the building and most worked on Saturdays ‘spreading the word’ across China.

American advertising agent Carl Crow was in his office down along the Bund on Jinkee Road, a short walk away from the Missions Building. Crow had arrived in China from Missouri just in time for the 1911 Republican revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty. He had become friends with Dr Sun Yat-sen, lived through China’s Warlord Era and had been an active member of the SVC in 1932 during the last Japanese threat to Shanghai. He was a veteran China watcher and a stalwart of the American community in the Settlement. That morning he sat at his desk and worked on a report for one of his major clients, Colgate. He sought to assure them that, despite ongoing skirmishes with Japan in Northern China, the Yangtze Valley and Shanghai remained calm with stable business conditions. He reminded them that their China sales were growing and that other American companies were also prospering in the city’s flourishing consumer market. He noted that sales of Kodak cameras, another of his major clients, were strong. For some time Crow had been considering whether to lease a beachfront property in the resort-city of Tsingtao as a holiday home to escape the humidity of oxygen-deprived Shanghai in summer. True, there had been some ‘little squabbles’ around the city – the current shelling of Chapei was one such – but there had been no major incidents.

He looked out of his window up at the storm-wracked skies over the narrow street below. Jinkee Road ran along the northern side of the Cathay Hotel, parallel with Nanking Road, and had transformed from a small lane of opium godowns into a street lined with modern office blocks populated by thriving foreign and Chinese commercial enterprises. Like Lucien Ovadia, Crow’s biggest problem that morning was staying awake and maintaining concentration in the airless humidity.

Carl Crow

Ellen Louise Schmid

Ellen Louise Schmid was standing on the roof terrace of the Cathay Hotel with her mother, Mary. Her Swiss father, Theodor (Theo), represented Anderson, Clayton in Shanghai, the world’s largest cotton traders based in Oklahoma City. The Schmids had a beautiful house on Amherst Avenue, in Shanghai’s leafier western district. Ellen had been raised in the Settlement and had written elegiac poems to the city as a young girl. Her life had been one of excitement. As well as living in the Far East’s most modern and cosmopolitan city, her last trip back to America had been aboard the Zeppelin Hindenburg from Germany to New York. She was now a senior at Stanford, back home visiting her parents for the summer. Her mother had taken her to the Cathay for tiffin as a treat. They stood on the roof of the hotel looking out across the Whangpoo, past the gunboats lining the river and over the marshlands out beyond the factories and godowns that crowded the Pootung shoreline on the opposite bank. Ellen’s mother had brought her new camera.

Eleanor B. Roosevelt & son Quentin

Several floors below the Schmids, Eleanor B. Roosevelt, former American President Teddy Roosevelt’s daughter-in-law, was dining with her son Quentin. They had arrived in Shanghai a couple of days before, having travelled from Nanking where Eleanor met with Madame Chiang. Eleanor knew the Far East intimately; her husband Theodore Roosevelt III, the former President’s oldest son, had been the Governor-General of the Philippines. Eleanor and nineteen-year-old Quentin were on a tour of the region. Quentin was interested in China, particularly in the Naxi people of Sichuan on whom he was planning to write a university paper. The two discussed their tour and considered a little sightseeing after lunch.

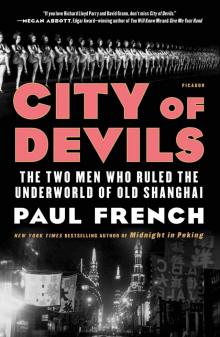

City of Devils

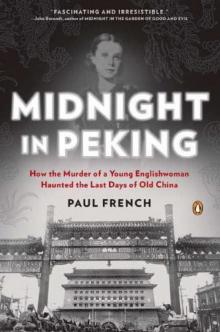

City of Devils Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China

Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China